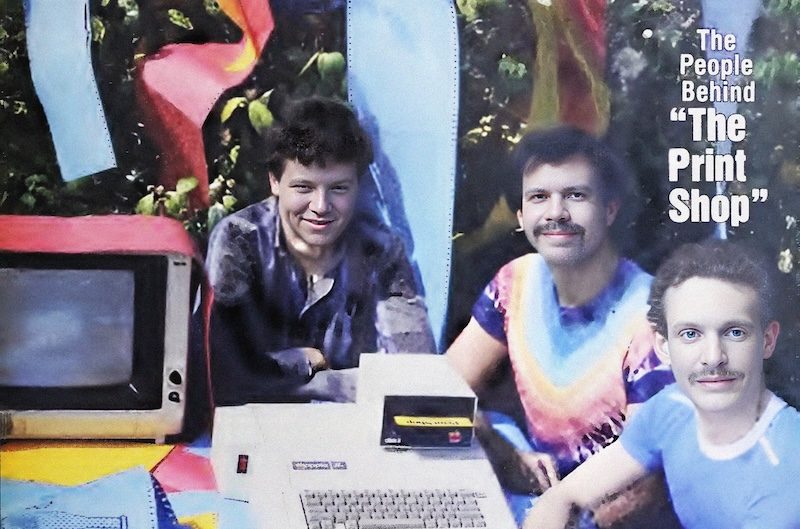

MICROTIMES APRIL 1985

“Everybody has talent. We just decided to help foment the revolution by liberating people’s artistic imaginations. Our own brand of subversive software.” David Balsam.

“We have a lot of fun with all the ideas that go flying around here. It’s sort of like reaching a creative critical mass.” Martin Kahn.

The home computer market is an interesting thing to study.

By examining the products being purchased by Joe Average Consumer you may discover things about society and personal priorities in the home computing environment. Check the top ten best seller lists of publications like Billboard, and you will find a most amazing phenomenon: the name Print Shop recurs frequently as the number one selling software package in America.

More popular than tax preparers, checkbook jugglers, stock market quote software, spreadsheets, music programs, and shoot ’em up games. The Print Shop. A program designed to create greeting cards.

In a world of H-bombs and diminished expectations, that’s the kind of trivia that makes it seem like there’s hope for humanity yet.

The Print Shop itself is far from trivial. It employs some of the most advanced graphic technology available on microcomputers and can be used by anyone in a matter of minutes without consulting the documentation or knowing any more about computers than the location of the power switch.

Print Shop is totally menu driven and can be used to create greeting cards, letter heads, stationery, posters, signs and banners of any length by simply choosing and arranging various graphic elements using the key board, joystick, or KoalaPad.

It features eight type styles in multiple sizes and in solid, outline and three dimensional formats, text editing, automatic centering, left and right justification, and proportional spacing. It has an onboard graphics library that contains nine border designs, ten abstract patterns, dozens of pictures and symbols, a selection of swirling animated patterns that can be frozen and used for an endless variety of background designs, a graphics editor that allows you to create your own images as well as modify the graphics in the “library’, and a selection of specially predesigned cards you can personalize at the touch of a button.

In addition, The Print Shop has a recently released companion disk called The Graphics Library, which has 120 images stored on both sides, all of which can be arranged in the same manner as Print Shop images (it is important to note that the Library is only a file disk and can only boot a demonstration without the Print Shop disk).

What’s more, Print Shop can take images generated by any other graphics package and combine them with the Shop graphics or fonts, or just print them out as they appear, without the use of a Grappler Card or a utility program like ZoomGrafix.

The Print Shop and Graphics Library are available for the Apple II series (48K minimum), Commodore 64, and Atari, with versions planned for the Macintosh and IBM PC, XT, AT, PCjr, and their ubiquitous clones.

Print Shop will support virtually every major dot matrix printer on the market, and colored pin feed paper and ribbons can be ordered to really give your computer that certain artistic flair.

With all these options and abilities, The Print Shop is much more than a sophisticated toy. The applications are as varied as your imagination, and the popular acclaim has been astounding: the folder of fan mail and letters of commendation is over an inch and a half thick.

Some of the more exciting uses that Broderbund has heard about from grateful users include education (teaching spelling, art, and beginning computer literacy) and medicine (as an effective tool in the areas of physical, art, and cognitive therapy). That’s pretty impressive for any piece of software, let alone one that is commonly available in the $45-50 range, and this remarkable accomplishment has not gone un noticed by the industry analysts.

In 1984 alone, The Print Shop won six major awards from a broad field of admirers:

CES Software Show case— Outstanding Original Programming, Personal Productivity for the Apple (awarded by EIA/ Consumer Electronics Group);

October Software Best Seller— Home Management/Productivity (awarded by Home Computer & Software Merchandising);

Software Award Winner (awarded by Learning Magazine);

Program of the Year— Award of Excellence (awarded by Computer Entertainer);

Most Distinguished Computer Product (awarded by Enter Magazine);

Most Notable Award — Software of the Year Awards (awarded by the Classroom Computer Learning Magazine).

Obviously this is a pretty special program, and it speaks very well for its creators, Pixellite Software, or David Balsam and Martin Kahn (as it reads on their awards certificates and royalty checks)— two very special people with very different backgrounds.

David is a consummate musician, playing guitars, drums, and keyboards. He started his musical involvement at age 11 in New York City and has stuck with it for the past 18 years, with time out to take a couple of computer classes and earn a living as a software specialist and trainer for several computer specialty stores. As he puts it, “I never wanted an education to get in the way of my learning.”

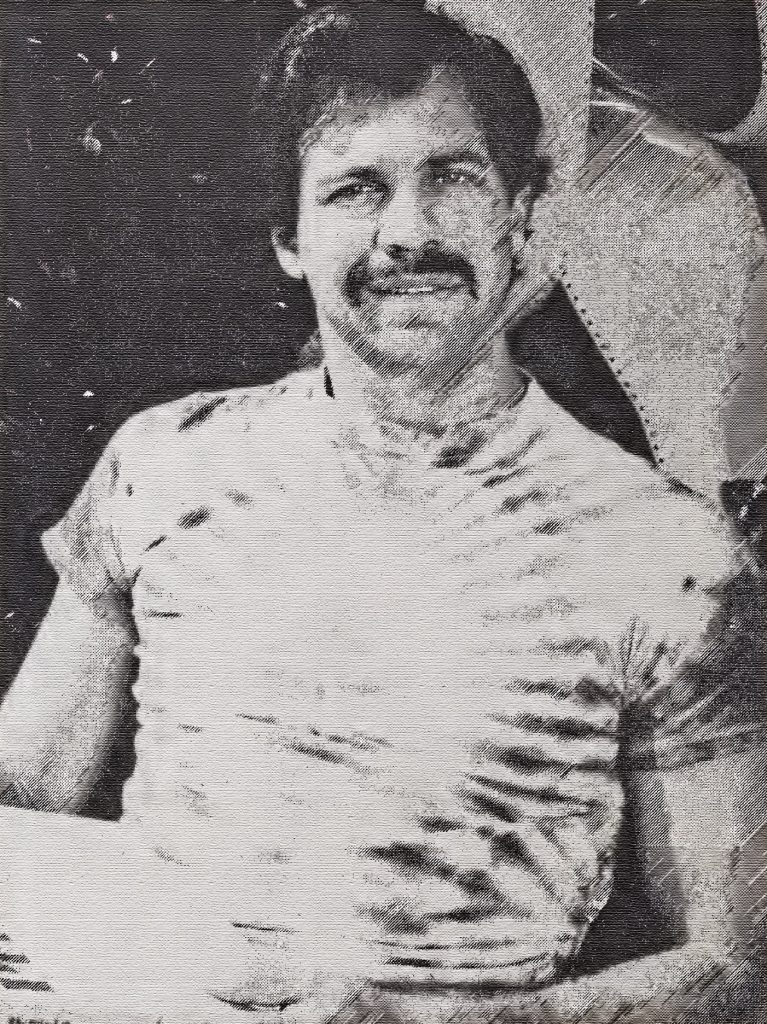

Martin Kahn

Martin is a native of Los Angeles, and a graduate of U.C. Berkeley with a double major in mathematics and linguistics. His primary interests lie in the arts, particularly in the areas of computer generated graphics and animation. He has worked as a graphics programmer for Northstar Computer and Broderbund Software, and tried to make it as a “fine” computer artist in the gallery scene.

“A lot of so-called experts just don’t regard computer generated art as a real medium of human expression. They’re more than happy to sell lithos and prints and other examples of low tech reproduction, but they don’t seem to understand that there is as much, if not more, artistry in graphic programming as there is in oil painting. I’m good with a brush too, and I know this as a fact!”

Martin now finds himself quite busy as the main artistic force behind Pixellite Software, and though he won’t admit to it he seems to have a certain sense of amusement (or perhaps righteous vindication) at being one of the most widely distributed computer software artists in the world.

David and Martin met a couple of years ago at a party at Martin’s house. David was entranced by Martin’s artwork, which hung everywhere, obscuring the walls and more than one window. “When I first saw the paintings, my jaw very nearly hit the floor. They had the quality of an Escher or a Vaseralay, three dimensional shapes moving behind other shapes, distorted perspectives, fascinating topological landscapes. I knew then that there must be some commercial application for Martin’s talent.’

They became good friends before they started in partnership to produce software. Their first attempt didn’t get too far. David, the more vocal of the two, explains. “It seemed that there was a lot of beauty to computer enhanced graphics, a lot of things that people would like to be able to do for themselves, without being a computer whiz, or even an artist. So we thought we’d try to make a product out of it. Our first try was a greeting disk sort of a thing—the concept was to have some animation on the screen that would portray a message for special occasions, something with swirling 3D graphics, maybe play a song and have different messages flashing across the screen.

“We thought it would be fun to make something like that, so you could send it to a friend and they could put in on their computer and be amazed by it.”

It didn’t work. Actually it did work, but nobody wanted to publish it. “We called that one Perfect Occasion. It was, and still is, a good idea. I believe that there are now some people publishing similar programs. Our problem was that there was not a large enough installed user base— not everybody’s grandmother had an Apple then, and seriously, how many Valentines do you send to members of your user’s group?

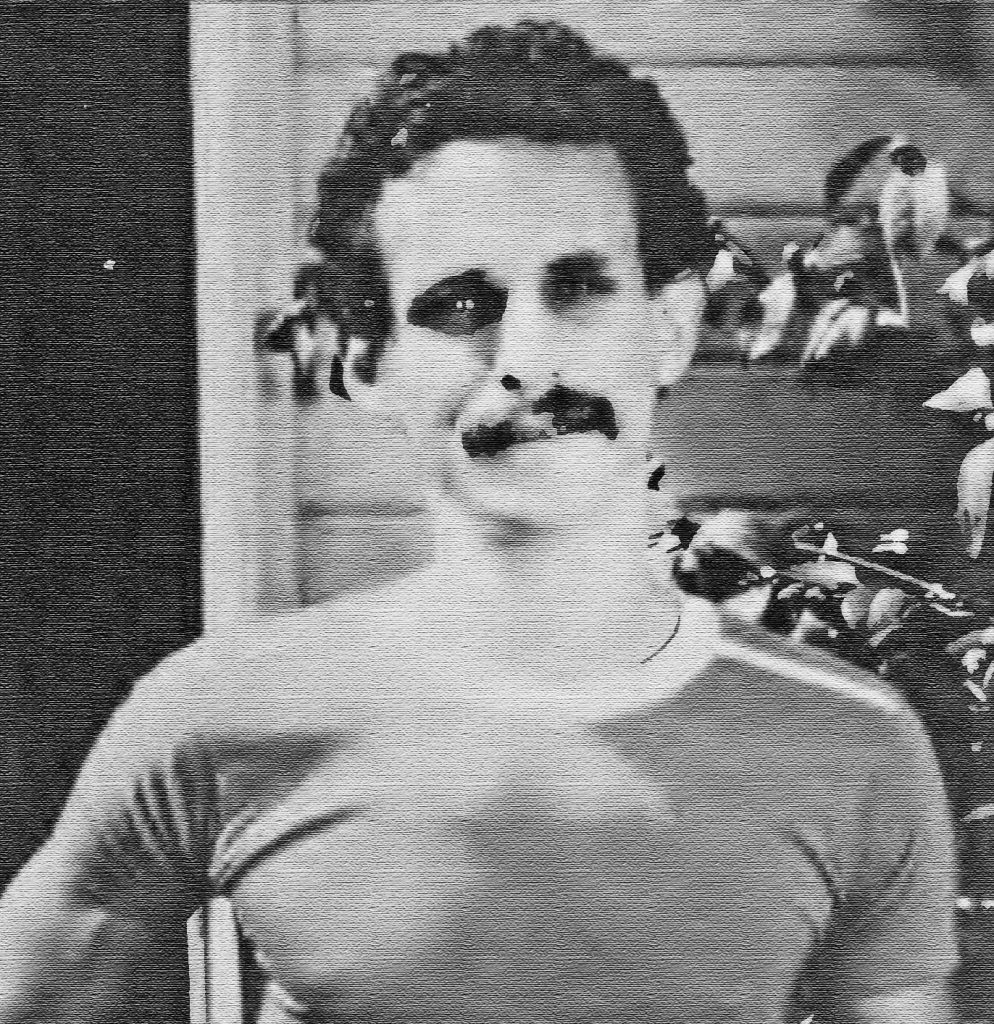

David Balsam

“Another problem we had was that the program was still too open ended— it relied too much on the drawing ability of the user. We began to realize that the audience we wanted to reach was not the sort of folks that like to doodle on paper or Graphics Magician or what have you, but more the sort that have been taught from birth that they have no talent, or just picked up that ludicrous notion somewhere along the line. Everybody has talent. Martin and I just decided to help foment the revolution by liberating people’s artistic imaginations. Our own brand of subversive software.

“In order to do this, we had to sort of formalize our working relationship. My greatest strengths are not in computing per se, but in organization—stepping back and getting the overview, and then being able to work from that view. Oddly enough, it’s a talent I developed as a musician and a composer. I understand structure and sequence. I became the software ‘director’ or architect.

“Martin is a brilliant artist and something of a programming genius. He started out writing programs for intelligent printers— to get ahead of the story a little bit, his experience is directly responsible for the quality of the printed image from Print Shop. All the images are stored in printer code, which affords a much higher resolution on the printout than graphics created on a screen-dedicated graphics program.

“At any rate, Martin and I formed an equal partnership and spent a year developing The Print Shop. We worked well together, and still do, but there were times…

“We eventually ended up with a product we were very pleased with. I don’t know exactly how to describe it— I cringe a little when I hear people describe it as a ‘friend’ — but it is a very pleasant experience to use, very gratifying and spontaneous. It’s easy to get excited about using it, it doesn’t ask too many questions of you, it doesn’t demand anything.

“It works more by presenting you with a scenario that enables a part of you, an explorative or creative part, to move out into a little world. In this case it’s The Print Shop, and it’s a little world of printing things. You’re led down this path of different ways of putting letters and images on a page. It breaks the world up into finite modules that are represented on the main menu for greeting cards and banners and such.

“It’s not an open system, like a MacPaint. It’s deliberately limited, but within those limits there is an infinite number of things you can do. It’s a real delicate balance of deciding where the limits are, and where is the openness. I’d say that the hardest part of designing a program is deciding what not to do.

“We started out with a lot of real good ideas, but given the concept of ThePrint Shop, which is graphic arts for the non-artist and non-graphics oriented person, we couldn’t use them all. You can’t give our target audience that much of an open system— they’ll get lost in it, and that would soon re place fun with frustration, totally defeating the purpose of the program!’

Corey Kosak

There is the roar of a Porsche 924 from the driveway. Martin goes to the window and announces, “Corey’s here!’ A moment later Corey Kosak walks in, grinning nervously and holding the detached front doorknob in his left hand. A few comments about Berkeley landlords later, the interview resumes, with Corey taking up the narrative.

“I got involved with Pixellite a little later in the game—I’m not a partner, I guess you could say I work for them I started work at Broderbund Software in 1981, and when they needed an Atari version of The Print Shop, they asked me to do it. Around the middle of that project, Broderbund decided that the Commodore version was more important— so I did that. It turns out that the Commodore printers are like nothing else on the planet, so I wrote the drivers for them, and Martin took care of the more conventional printers. Then I went back and finished the Atari version. I just completed that last week in time to be free for my nineteenth birthday!’

He blushes slightly and continues. “I guess I’m what you would call a whiz kid. I started playing with computers in the sixth grade. The junior high school had just gotten hooked up with a couple of teletype machines, and my math teacher thought it was a good idea to send me over there to play with them. I played Hangman and Star Trek and all of those. Then I started hanging around Radio Shack. The TRS-80 had just come out, and nobody knew any thing about it, so I sat in the back of the store and tried to figure it out.

“That’s where I got my real programming experience, reading all those Radio Shack manuals and just playing with the machine. The next step happened when the Apple II came out. Some businessman went out and bought one, and then called Radio Shack for advice. The salespeople introduced him to me, and this guy lent me his Apple for six months. It was great— I kept on calling him up, telling him I needed a second disk drive, an eighty column card, all the goodies, and he would get them for me.

“In exchange I wrote him some little financial program. I was fourteen then. Next I got involved in the Marin Computer Center, where you could rent computer time for real cheap. I met the director, David Fox, there and it was with him that I developed my first commercial piece of software, a program called AppleSpice, which was designed to extend and to fill the holes in Applesoft Basic.

“I met Doug Carlston (president of Broderbund) at an Apple Corps meeting where I was demonstrating AppleSpice. After talking business for a while, he lent me a complete Apple II system. I’ve been with Broderbund ever since.

“It’s kind of funny— all this time I had still not bought a computer, people just kept on giving them to me. I still have that system too…. I guess they’ll make me buy it one of these days, but if things keep on going the way they have been, I’m not going to worry — I’m pretty much booked up for the next few years!”

David chimes in. “If I could have my pick of Broderbund’s stable of programmers to work with, I would choose Corey. And he’s doing it! We’re all real excited about having him with us. As a matter of fact we’re working with a lot of really excellent people — Chris Jochumson who wrote Space Quarks, Track Attack, Arcade Machine and did a lot of graphic work with Penguin Software’s Roland Gustaffson, a hotshot utilities program mer; Don Williams, who worked on Music Shop and PFS File and Report; David Snyder, author of Serpentine, Dazzle Draw, and David’s Midnight Magic; and Gini Shimabukuro, a graphics designer and computer classroom instructor.

“This is a real exciting group. We have a lot of fun with all the ideas that go flying around here. It’s sort of like reaching a creative critical mass. There is no end to the number of really good projects we are coming up with, and the new crop of machines entering the market has expanded our potential applications astronomically. I mean that literally. One of our pet projects,” he said smiling and patting a large stack of colored paper, “is right here. After this next round of development, we intend to invade Alpha Centauri to expand our market!”

In addition to designing software, Pixellite has branched out into the computer supply arena, particularly in products that support The Print Shop. The business seems to be doing exceptionally well — in a period of five months it’s gone from two employees to twenty, and the orders are pouring in from all over the world.

This is in large part due to the tremendous success of The Print Shop, and to the unusual nature of Pixellite’s products—they are the sole supplier of color computer paper. Marketed under the brand name Brite Line, their high quality, heavy weight continuous form paper is available in eight colors (red, green, blue, pink, gold, yellow, pure white, and tan parchment); matching envelopes come in greeting card and #10 sizes. Pixellite also markets various sizes of printer ribbons in red, blue, green, purple, brown, and black — every thing you need to get the most out of your Print Shop or other software program. You can order a healthy sized Rainbow Sampler Pack for under forty dollars. The ribbon prices vary with the quantity and the printer. Turnaround time on orders is about 48 hours unless special rush orders are specified. The catalog is free and is available by calling or writing: Pixellite Computer Products 5221 Central Ave., Suite 205 Richmond, CA 94804 (415) 527-6400 1-800-643-0800 (credit card orders)